Treatment & Monitoring

Treatment for Cushing's Disease

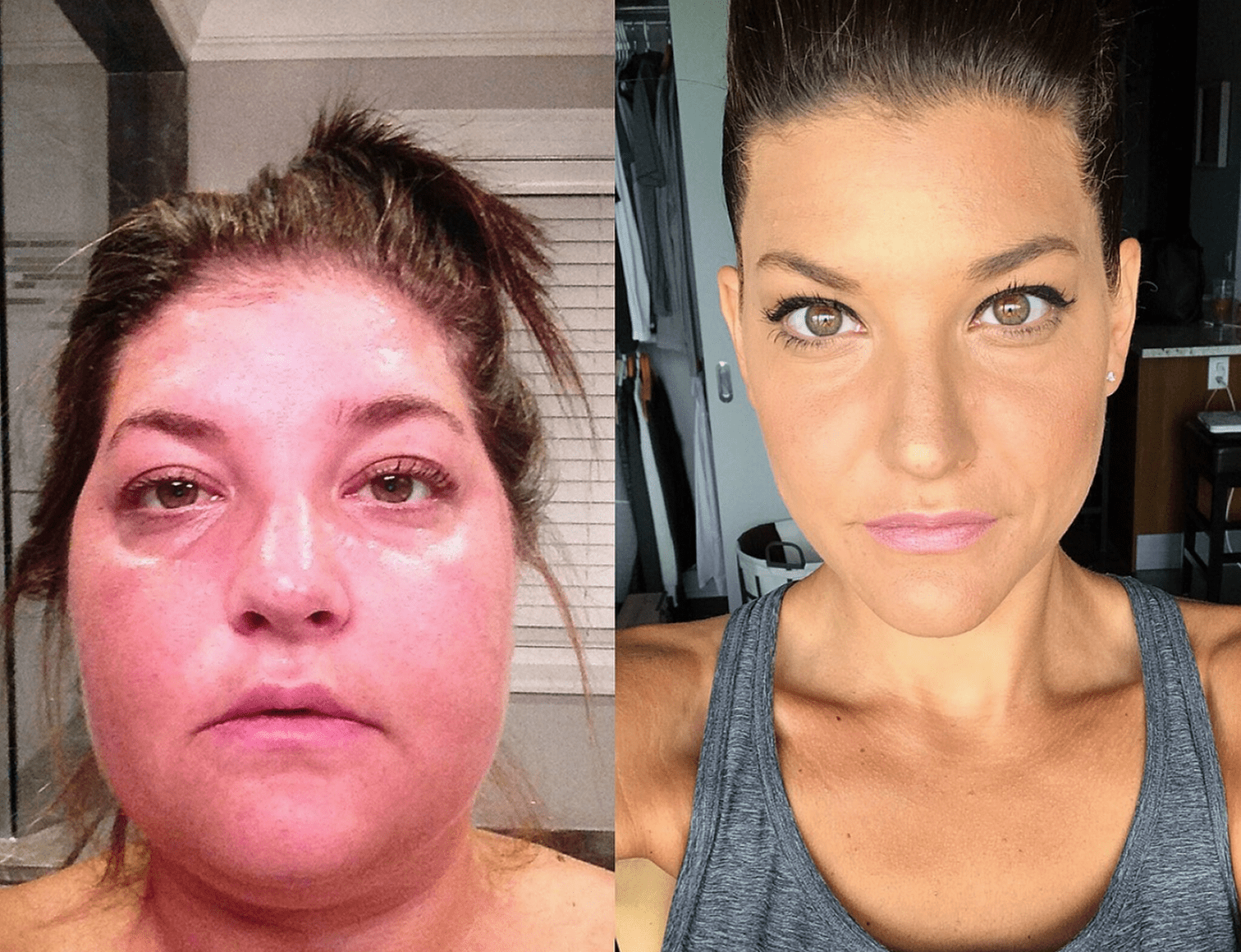

Diagnosis in Cushing’s disease: A rare challenge.

Cushing’s disease (CD) is often overlooked, with an average time to diagnosis of 7 years.1,2<

Treatment & Monitoring

Diagnosis in Cushing’s disease: A rare challenge.

Cushing’s disease (CD) is often overlooked, with an average time to diagnosis of 7 years.1,2<

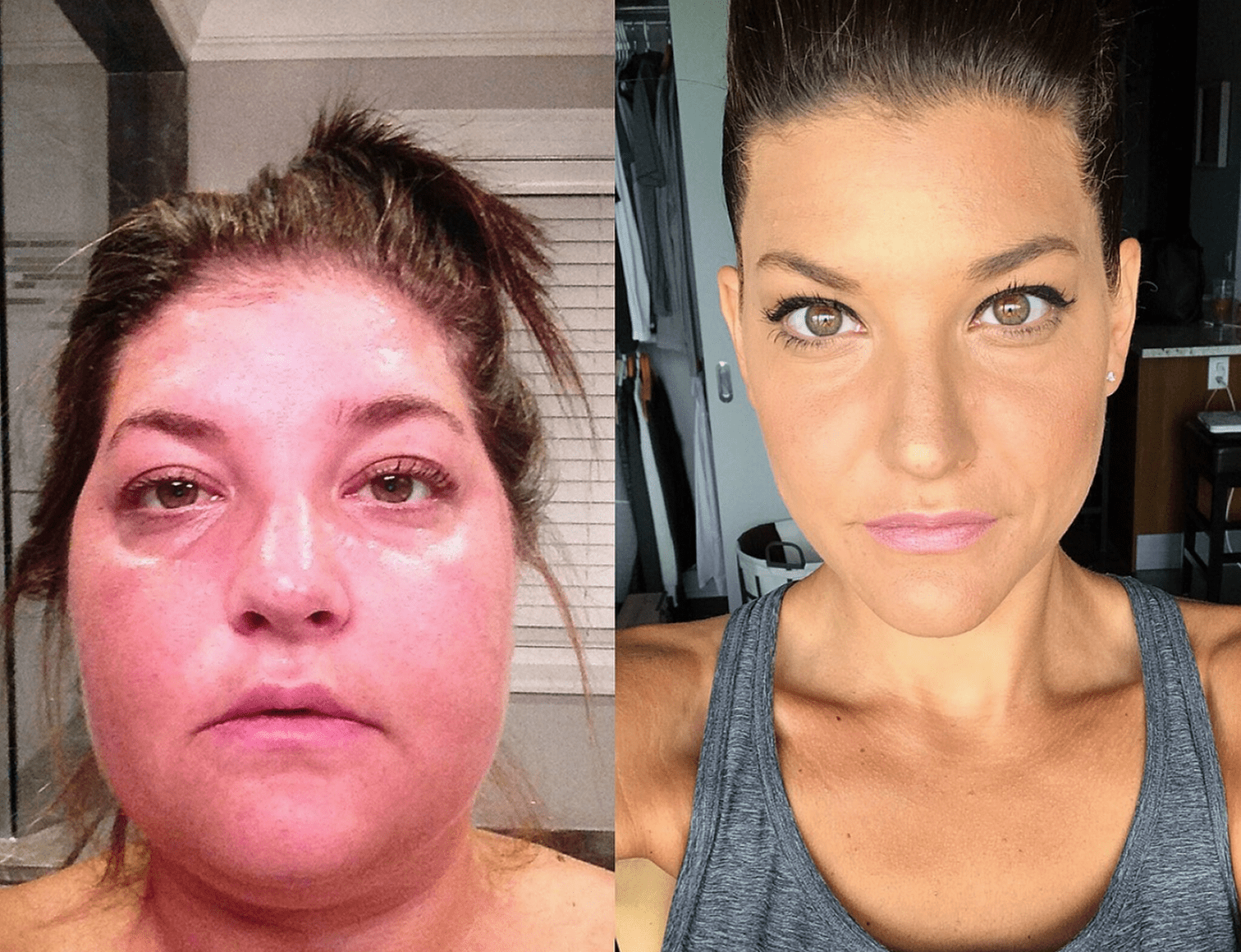

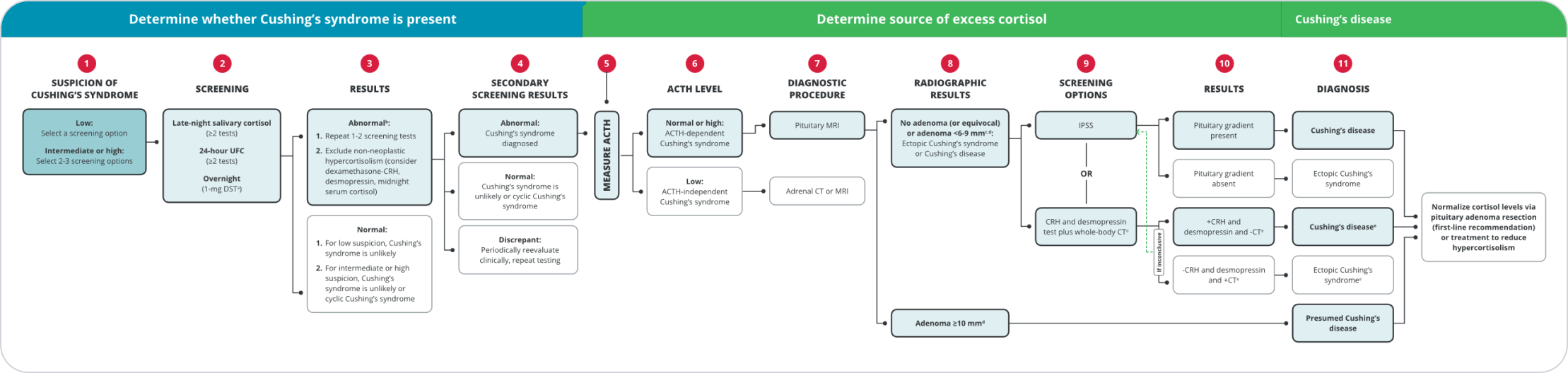

Steps

While some features are more discriminatory to indicate Cushing’s syndrome (CS), diagnosis of CD begins with screening for elevated endogenous cortisol.3-5

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; CT, computed tomography; DST, dexamethasone suppression test; IPSS, inferior petrosal sinus sampling; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; UFC, urinary free cortisol.

aCan also use the 48-hour, 2-mg/d low-dose DST. May deliver more accurate results than other tests when certain psychiatric conditions, morbid obesity, alcoholism, and diabetes are present.6

bConsider psychiatric disorders, alcohol use disorder, pregnancy, severe obesity, polycystic ovary syndrome, uncontrolled diabetes, anorexia, malnutrition, excessive exercise, illness or surgery, high corticosteroid-binding globulin state, glucocorticoid resistance.3

cOn average, 20% to 50% of pituitary adenomas are not visible on MRI.7

dThere is consensus that all patients with lesions <6 mm in diameter should have IPSS and those with lesions of ≥10 mm do not need IPSS, but expert opinions differ regarding tumors 6 to 9 mm in diameter.3

eThis option does not have clear consensus and needs further research.3

Tests

Late-night salivary cortisol (LNSC) test

At least 2 to 3 tests recommended. Sample at regular bedtime. Not recommended in patients with abnormal day/night cycles. Confirm which type of laboratory assay to use (immunoassay or LC-MS).3

24-hour UFC

Perform at least 2 to 3 screenings. Results should take into consideration the sex, BMI, age, urinary volume, and sodium intake of the patient.3

Overnight 1-mg DST

Test at 8 AM after 1-mg dexamethasone has been administered between 11 PM and midnight.3 Should not be used in pregnant women.6 False-positive rates for the overnight DST (1 mg and 2 mg) are seen in 50% of women taking oral contraceptives.6 Normal response: serum cortisol concentration <1.8 μg/dL (50 nmol/L).3 False positives are common; measuring dexamethasone concomitantly with cortisol can reduce risk of false positives.3

48-hour, 2-mg/d DST

Administer dexamethasone 0.5 mg every 6 hours for 48 hours, beginning at 9 AM on Day 1.6 Should not be used in pregnant women.6 False-positive rates for the overnight DST (1 mg and 2 mg) are seen in 50% of women taking oral contraceptives.6 Normal response: serum cortisol concentration <1.8 μg/dL (50 nmol/L).3 False positives are common; measuring dexamethasone concomitantly with cortisol can reduce risk of false positives.3

IPSS

Measures ACTH levels in the pituitary gland vs ACTH levels in the peripheral blood; the gold standard test to determine if the source of ACTH is from the pituitary gland or an ectopic source. Should be performed in a specialized center.3

CRH screening

Measures response to an intravenous bolus injection of recombinant human or ovine-sequence CRH at doses of 1 μg/kg of body weight (or total dose of 100 μg).8

Desmopressin test

ACTH-secreting adenomas express vasopressin 3 receptors, which produce an increase in plasma ACTH concentration after desmopressin injection. Has a high specificity for Cushing’s disease.3 ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; BMI, body mass index; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; DST, dexamethasone suppression test; IPSS, inferior petrosal sinus sampling; LC-MS, liquid chromatography mass spectrometry; UFC, urinary free cortisol.

TESTS & DIAGNOSIS

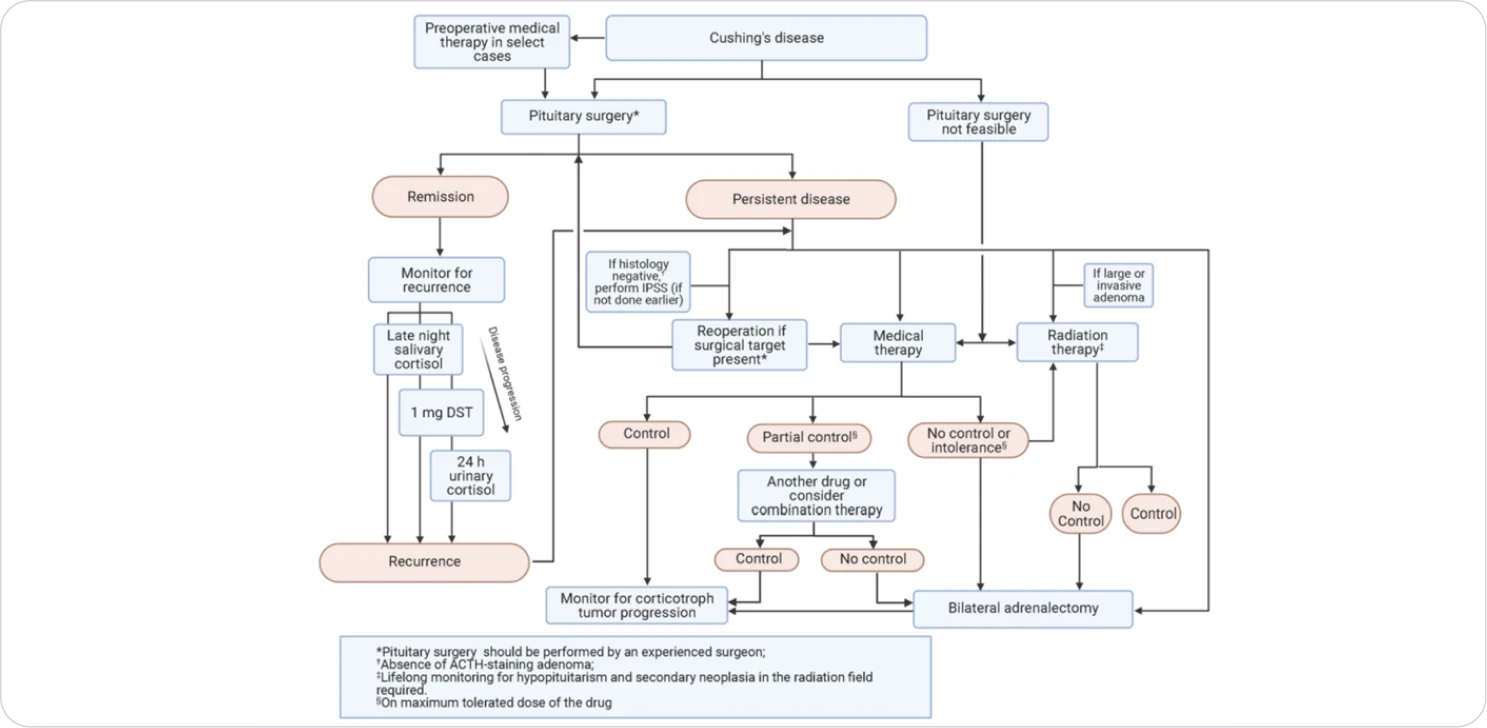

MANAGEMENT

Algorithm for management of Cushing’s disease. Abbreviations: ACTH, adrenocorticotropin; DST, dexamethasone suppression test; IPSS, inferior petrosal sinus sampling.

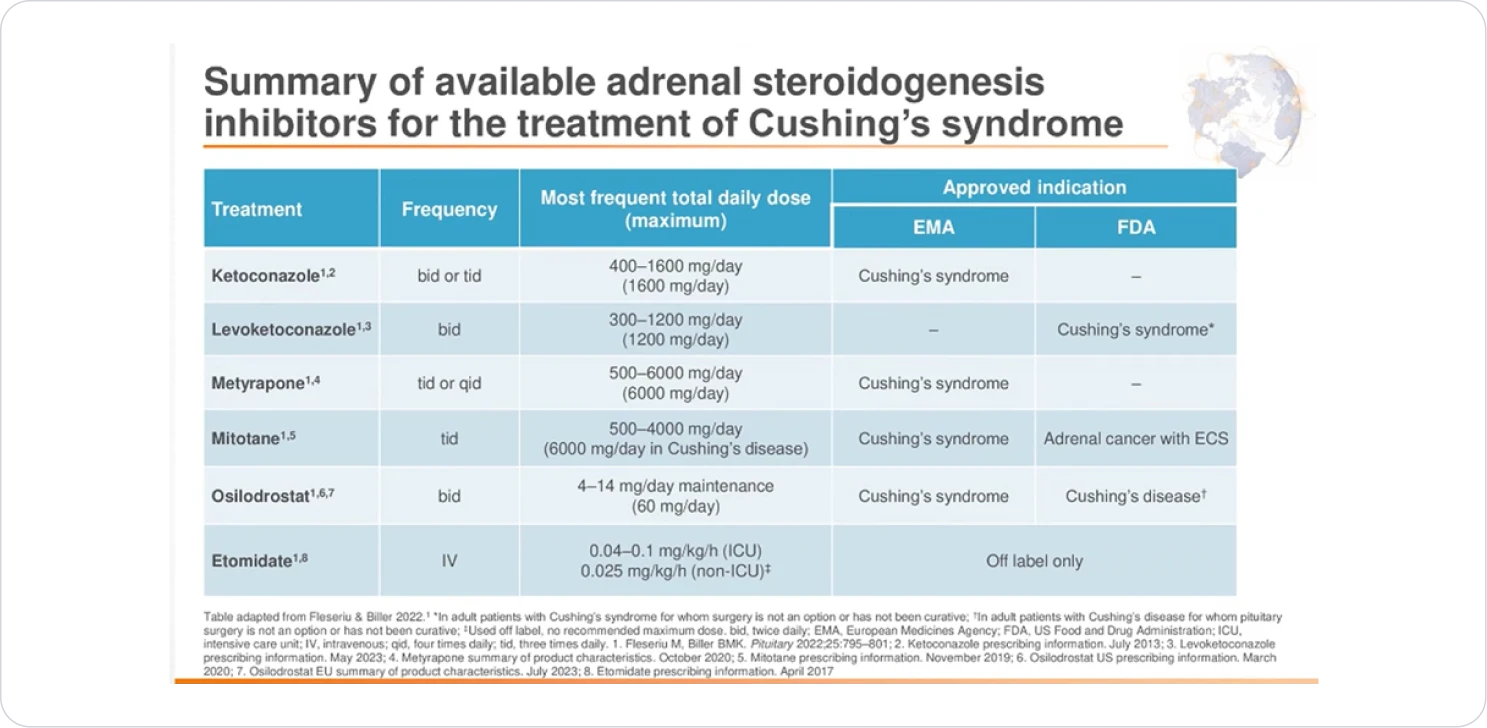

TREATMENT

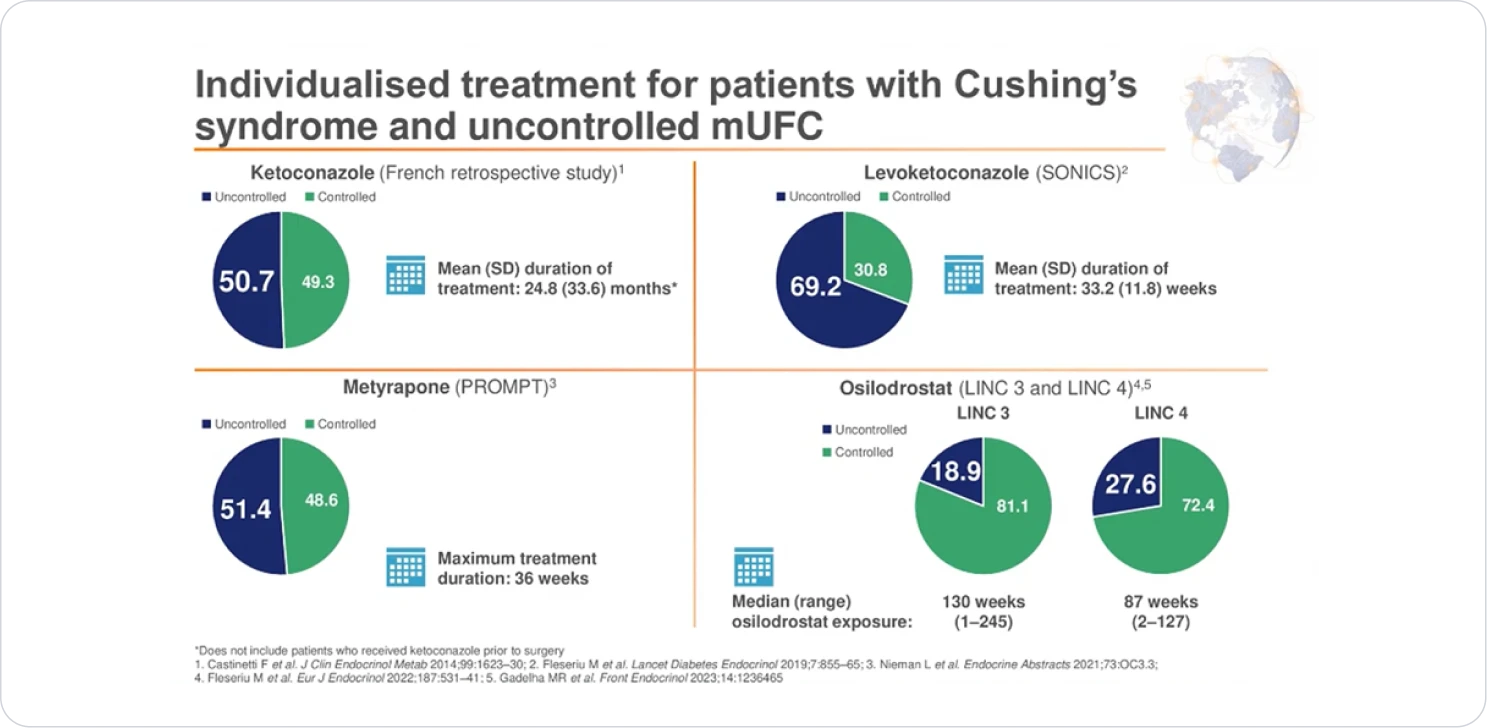

INDIVIDUALISED TREATMENT

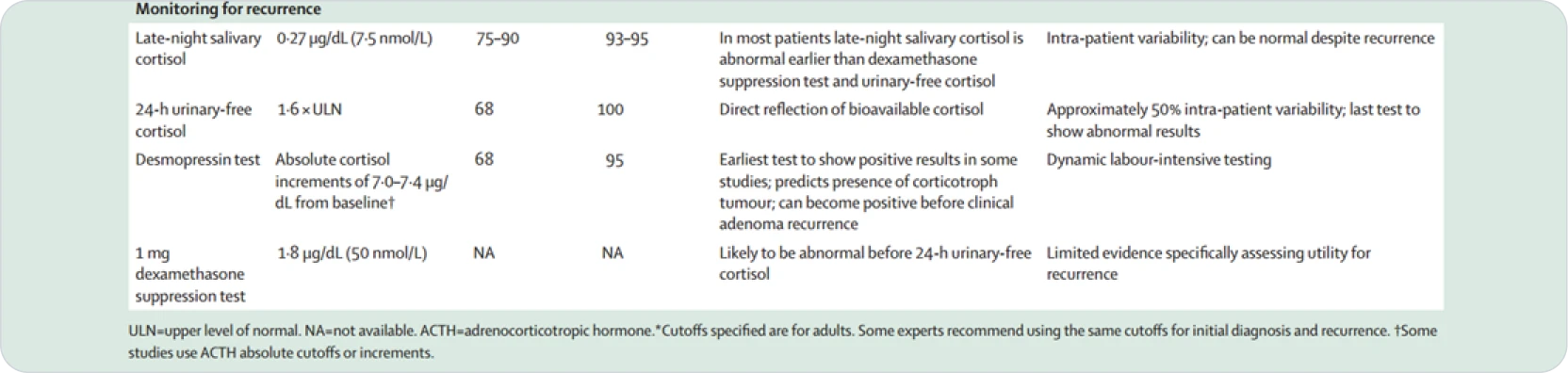

MONITORING

• Consider which tests were abnormal at initial diagnosis

• LNSC most sensitive, should be done annually

• DST and UFC usually become abnormal after LNSC

• UFC is usually the last to become abnormal

Diagnose CD

As soon as you diagnose CD, it is critical to initiate treatment to minimize further complications9. Surgery is the first-line treatment for CD, but may not be curative3

While pituitary surgery is the recommended first-line treatment for CD, recurrence after surgery is common.3

The high incidence of CD recurrence necessitates annual clinical and biochemical follow-up, or sooner if there is clinical suspicion for recurrence3,10

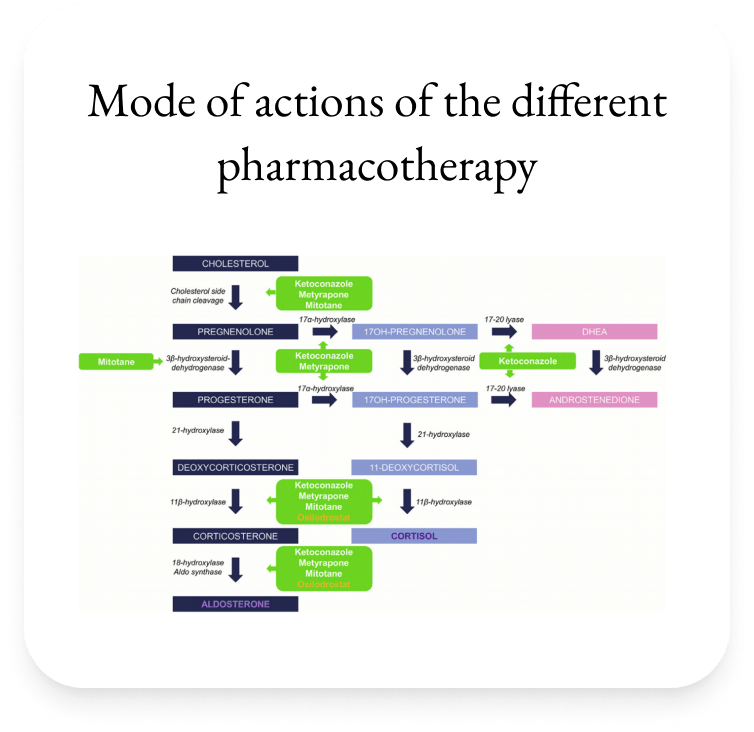

Pharmacologic therapy is a potential treatment choice for patients for whom surgery is not an option or has failed to effectively normalize cortisol3

≈25%

up to 5 years9

≈26%

up to 13 years10

May be appropriate for:

Patients who have refused or are ineligible for surgery3

Patients with persistent or recurrent CD3

Patients undergoing radiotherapy who require further control in cortisol levels3

*Persistent comorbidities despite remission could increase mortality11

| Therapeutic Area | Therapeutic Class | Efficacy | Possible Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pituitary gland | Somatostatin analogues (SSA) e.g. Pasireotide | ~40%* | Nausea, diarrhoea, gallstones, hyperglycaemia* |

| Dopamine agonist e.g. Cabergoline | 28-40%β | Asthenia, Nauseaβ | |

| Adrenal Gland | Steroidal genesis inhibitor e.g Ketoconazole | >50%§ | Elevated liver enzyme, Gastrointestinal disorders, hypogonadism§ |

| Metyrapone | >50% | Hirsutism, hypokalaemia and Hypertension (high dose)π | |

| Osilodrostat | ~86%€ | Nausea, anemia, arthralgia and headache€ | |

| Adrenolytic drug e.g. Mitotane | 72%# | Gastrointestinal disorders, asthenia, rashes, neurological disturbances, increased liver enzymes, hypercholesterolemia and isolated thyrotropic insufficiency# | |

| Serum Cortisol | Glucocorticoid receptor blocker e.g. Mifepristone | 38-60%* | Nausea, asthenia, metrorragia, hypokalemia¥ |

#Baudry C, Coste J, Bou Khalil R, et al. Efficiency and tolerance of mitotane in Cushing's disease in 76 patients from a single center. Eur J Endocrinol 2012;167:473e81

*Lacroix A, Gu F, Gallardo W, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-monthly pasireotide in Cushing's disease: a 12 month clinical trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;6:17e26.

βFerriere A, Cortet C, Chanson P, et al. Cabergoline for Cushing's disease: a large retrospective multicenter study. Eur J Endocrinol 2017;176:305e14.

§Castinetti F, Guignat L, Giraud P, et al. Ketoconazole in Cushing's disease: is it worth a try? J Clin Endocrinol Metabol 2014; 99:1623e30.

πDaniel E, Aylwin S, Mustafa O, et al. Effectiveness of metyrapone in treating Cushing's syndrome: a retrospective multicenter study in 195 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol 2015;100:4146e54.

¥Fleseriu M, Biller BMK, Findling JW, et al. Mifepristone, a glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, produces clinical and metabolic benefits in patients with Cushing's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol 2012;97:2039e49.

€Biller BM, Newell-Price J, Fleseriu M, et al. (LINC 3). OR16-2 osilodrostat treatment in Cushing's disease (CD): results from a phase III, multicenter, double-blind, randomized withdrawal study. J Endocr Soc 2019;3

Disclaimer:The information is based on study publications and is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice

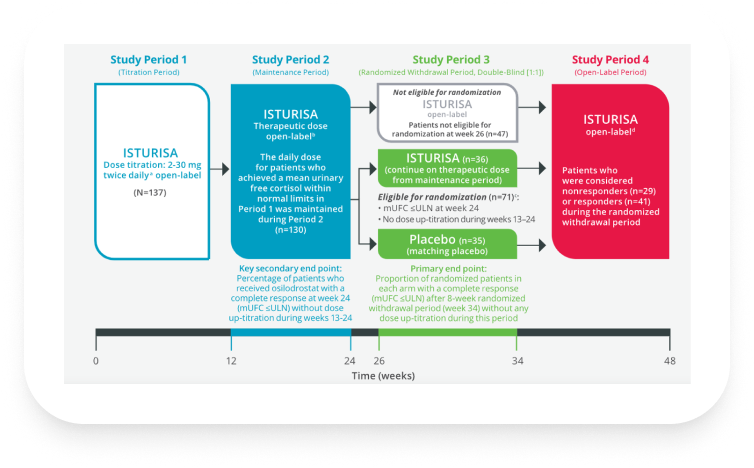

Osilodrostat study: LINC 3 was a phase 3 clinical trial in patients with Cushing’s disease (CD) (N=137) that included a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal period1,3

| Inclusion criteria1,3 |

|---|

| Patients aged 18 to 75 years with a confirmed diagnosis of persistent, recurrent, or de novo (if not surgical candidates or refused surgery) Cushing’s disease |

| Confirmed Cushing’s disease as determined by mean of 3 UFC concentrations of >1.5 x ULN at screening |

| Patients with a history of pituitary surgery had to be at least 30 days post surgery |

| Evidence of a pituitary source of excess ACTH |

| Baseline characteristics1,3 |

|---|

| Mean age at enrollment was 41 years |

| 77% (106/137) of patients were female |

| 88% (120/137) of enrolled patients had previous surgery |

| Mean of three 24-hour mUFC at baseline was 365 μg/24 h (≈7 x ULN) |

| Median mUFC was 173 µg/24 h (≈3.5 x ULN) |

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; mUFC, mean urinary free cortisol; UFC, urinary free cortisol; ULN, upper limit of normal.

aDose was up- or down-titrated every 2 weeks if mean urinary free cortisol (mUFC) was greater than upper limit of normal (ULN; defined as 138 nmol/24 h or 50 μg/24 h) or if mUFC was lower than lower limit of normal (LLN; defined as 11 nmol/24 h or 4 μg/24 h), respectively.1

bDose adjustments were permitted during Study Period 2.1

cPatients who did not require further dose increase, tolerated the drug, and had mUFC levels ≤ULN at week 24 were considered responders and eligible to enter the randomized withdrawal period. Patients whose mUFC became elevated during the maintenance period could have their dose increased further, if tolerated, up to 30 mg twice daily. These patients were considered nonresponders and did not enter the randomized withdrawal period, but continued open-label treatment together with the patients who did not achieve normal mUFC levels at week 12.1

dPatients remained on assigned dose throughout the randomized withdrawal period if their mUFC levels were within normal limits (WNL). Blinded dose reduction or temporary discontinuation for safety or tolerability issues were permitted; however, dose increases were not permitted. Patients with mUFC levels >1.5 x ULN or who required a dose increase were considered nonresponders and discontinued from the randomized withdrawal period but allowed to receive open-label treatment during the open-label period.1

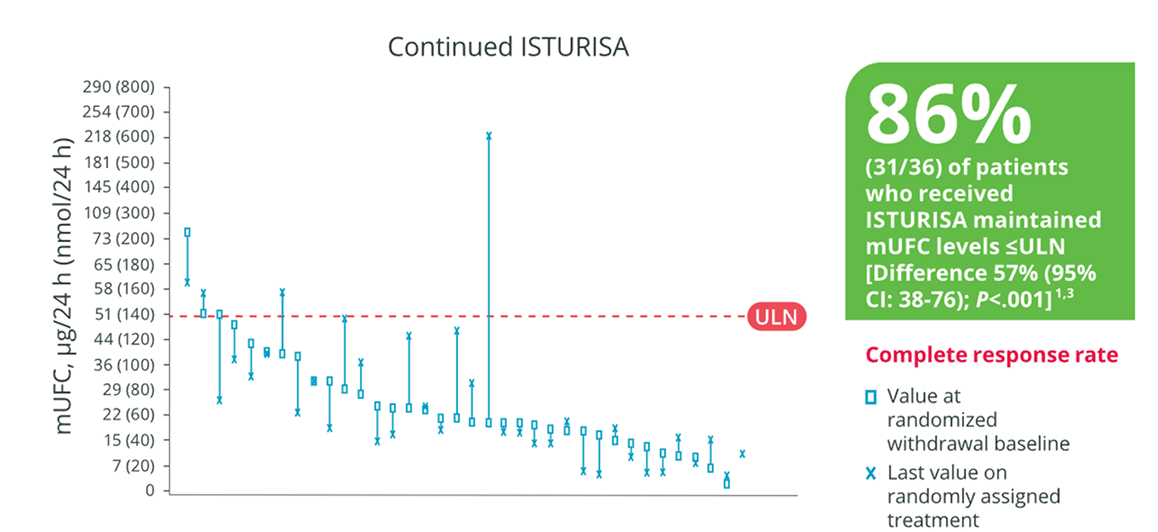

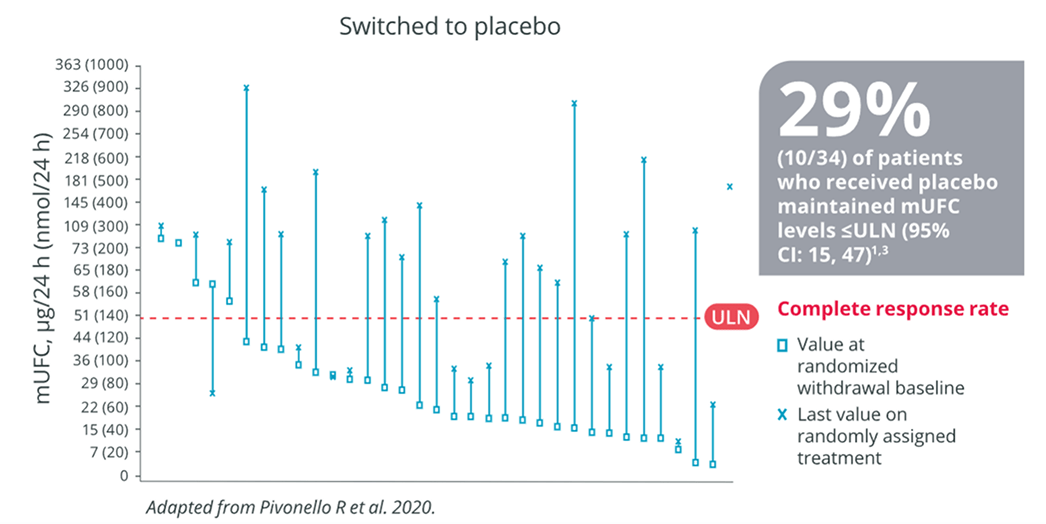

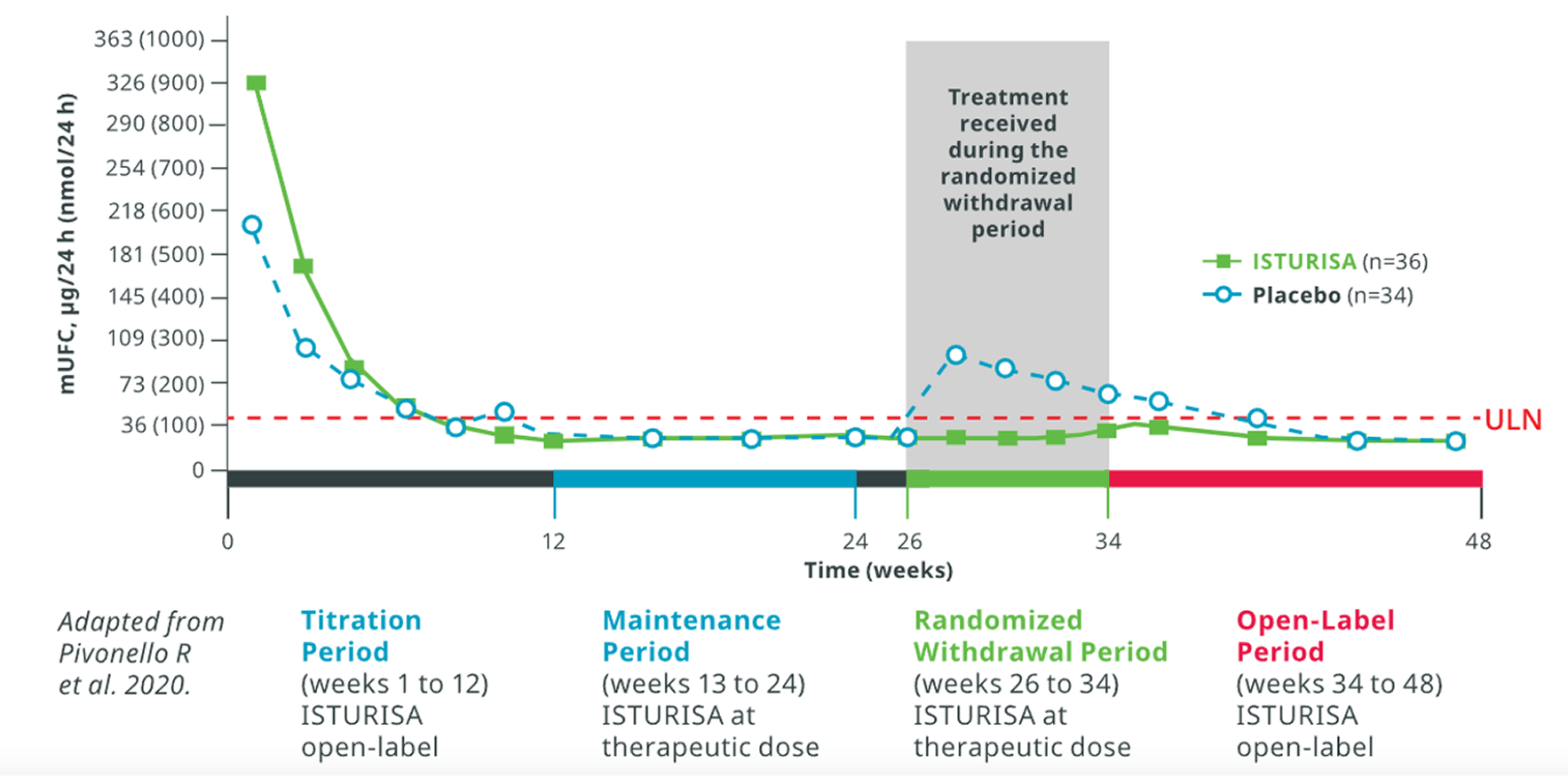

ISTURISA maintained normalization of mUFC in a majority of patients in the randomized withdrawal period3

Demonstrated superiority over placebo at maintaining mUFC ≤ULN at the end of the randomized withdrawal period[n=71, Difference 57% (95% CI: 38-76); P<.001]1,3

Primary End Point1,3

Complete responder ratee after 8-week randomized withdrawal period (week 34)

eComplete responder rate at the end of the randomized withdrawal period was the percentage of patients who had mUFC levels ≤ULN (defined as 138 nmol/24 h or 50 μg/24 h) at the end of the randomized withdrawal period (week 34), and who neither discontinued randomized treatment or the study nor had any dose increase above their week 26 dose.1,3

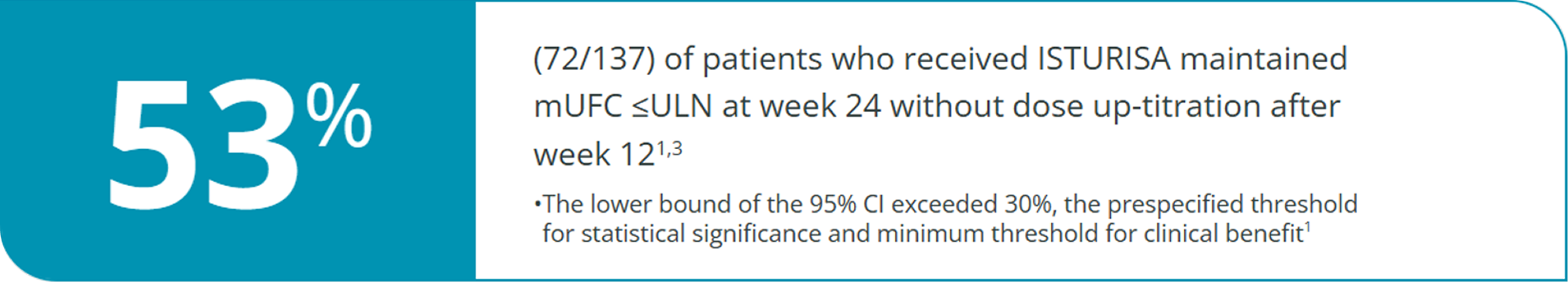

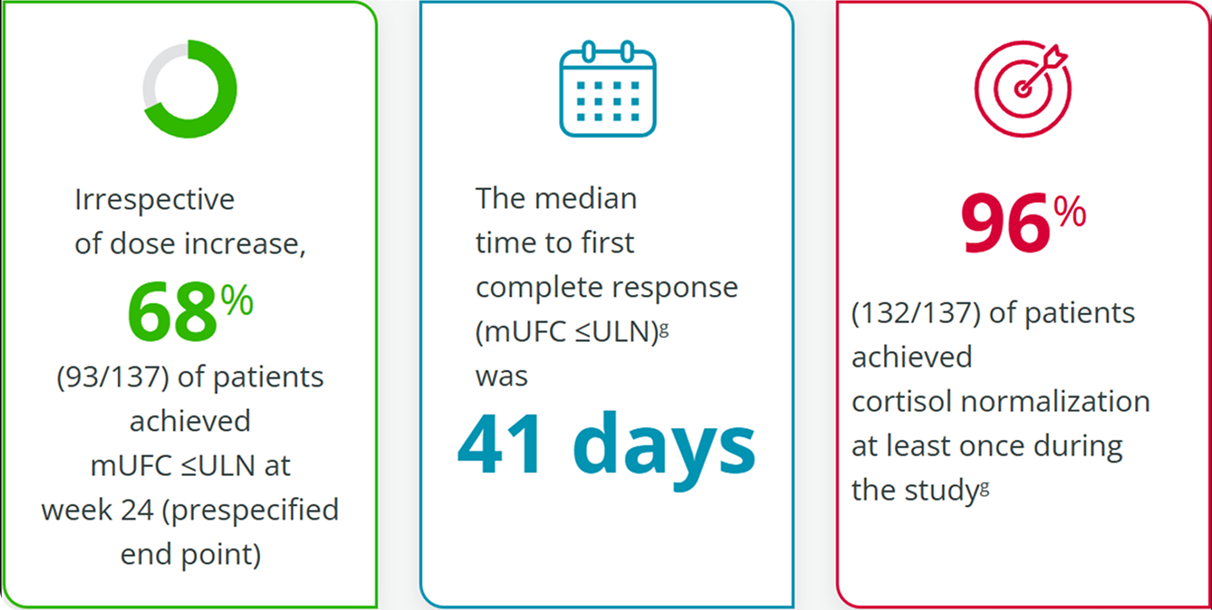

ISTURISA works to normalize mUFC levels1,f. More than half of patients maintained normalized mUFC with ISTURISA at the therapeutic dose established during the titration period1

Key Secondary End Point1,3

Complete responder rate at week 24 (end of maintenance period)

Additional Analysis Indicate Other Signs of Improvement with Isturisa1

The ULN for UFC was defined as 138 nmol/24 h or 50 μg/24 h.1These data were not included in primary or secondary end point analyses and were assessed post hoc; therefore, no definitive conclusions should be drawn.1,3

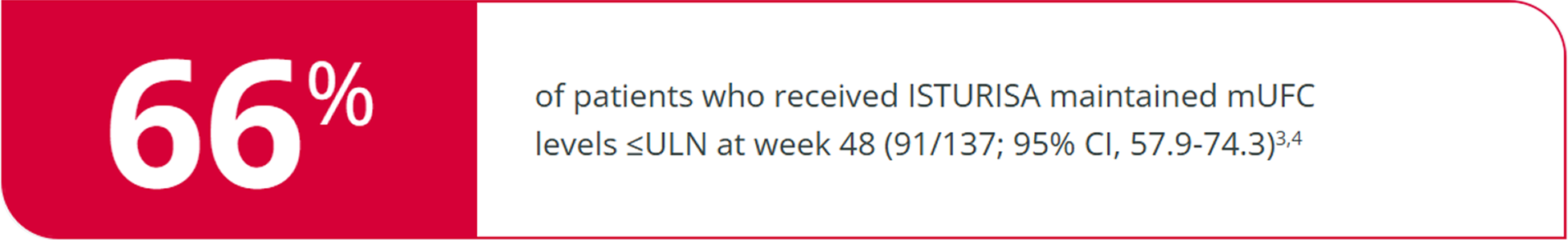

ISTURISA sustained normal mUFC up to 48 weeks in a majority of patients3. In patients who received ISTURISA, mean mUFC decreased rapidly during the titration period, then remained below baseline through week 484

48-Week Study End Point1,3

ITT analysis, end of open-label period

Mean mUFC At Time Points Up to Week 48

among all patients who received treatment in the randomized withdrawal period3

Average daily ISTURISA dose for all patients through 48 weeks was 10 mg/d5,

hAmong patients who were ineligible for the randomized withdrawal period, the average daily ISTURISA dose was 11 mg/d.5ITT, intention-to-treat; mUFC, mean urinary free cortisol.

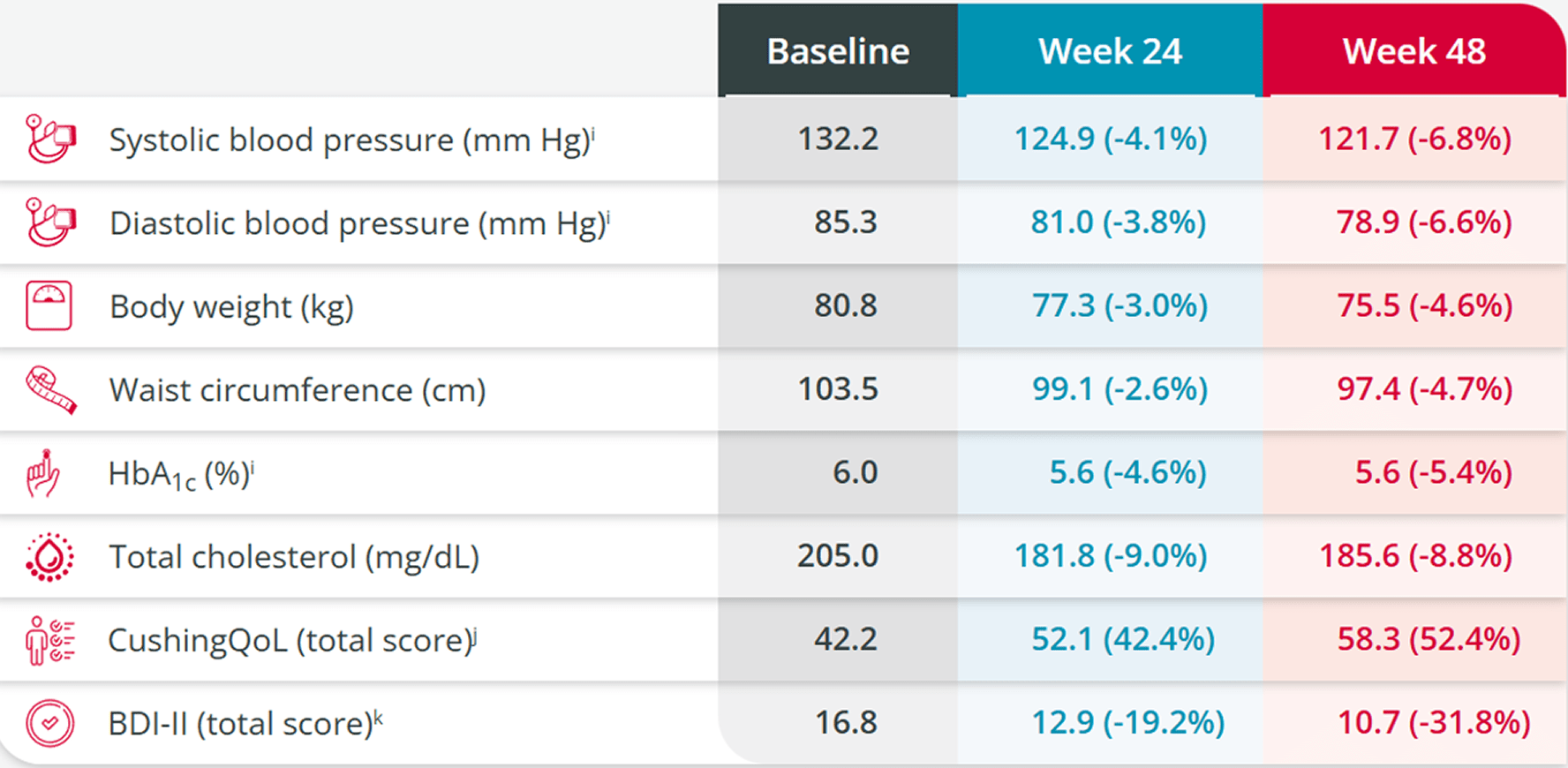

ISTURISA was associated with improvements in several secondary end points, including metabolic, health-related QOL (HRQOL), and depression parameters1,3

Mean Improvements

In patients taking ISTURISA, mean improvements were observed from baseline in the following parameters1,4,5

BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory; CushingQoL, Cushing Quality of Life; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin.

iStudy limitations: Because the study allowed initiation of antihypertensive and antidiabetic medications and dose increases in patients already receiving such medications and there was absence of a control group, the individual contribution of ISTURISA or of antihypertensive and antidiabetic medication adjustments cannot be clearly established.3

jCushing’s Quality of Life questionnaire (CushingQoL) is proven to be a reliable and valid instrument for measuring health-related quality of life (QOL) in patients with Cushing’s syndrome. Scores correlate with relevant clinical parameters.8The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) is a proven valid and reliable 21-item self-report multiple-choice inventory tool used to evaluate depressive states that occur at high prevalence among the medically ill.9

kImprovements were maintained during the 72-week open-label extension6

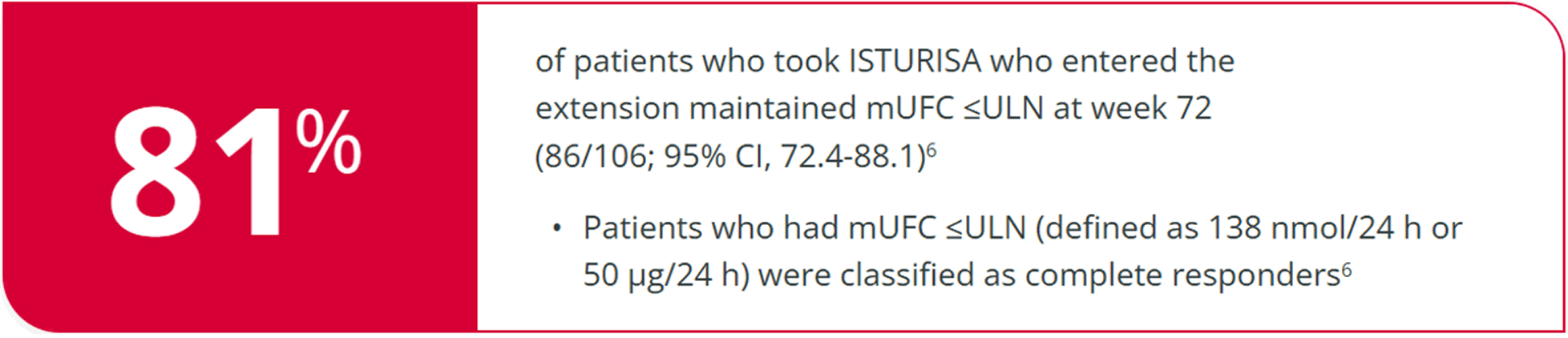

ISTURISA sustained normal mUFC for over a year in the majority of patients who entered the open-label extension (N=106)6

Linc 3 Extension Results6

Complete responder rate at week 72

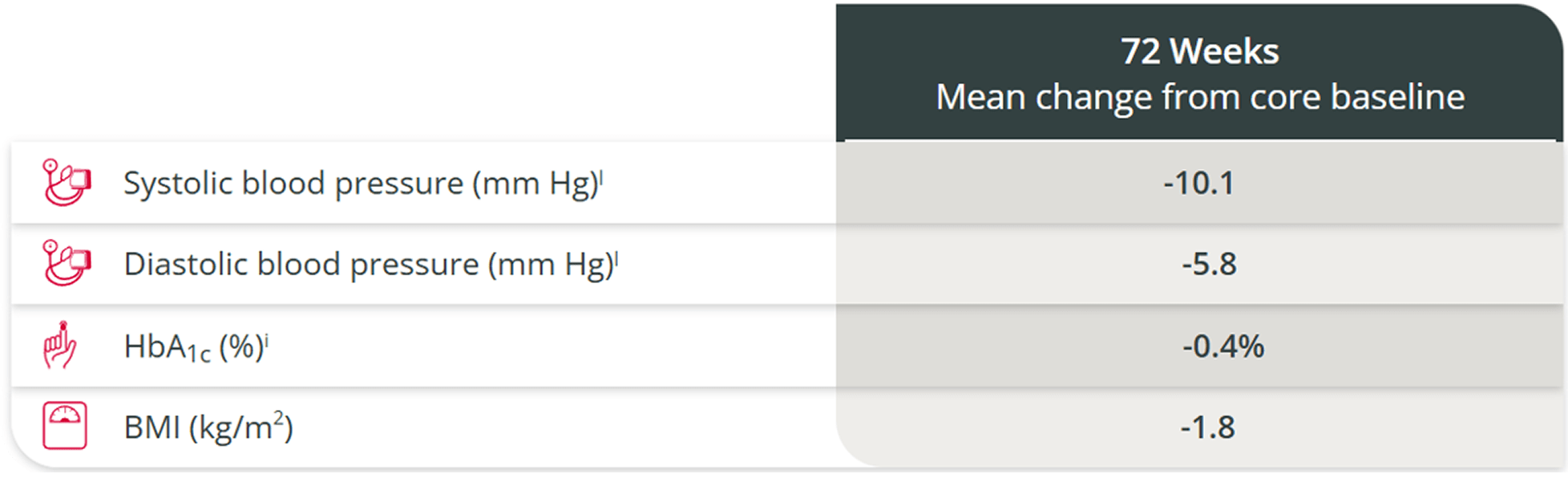

Improvements in cardiovascular-related parameters

were maintained through the open-label extension1,6,l

BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin.

Because the study allowed initiation of antihypertensive and antidiabetic medications and dose increases in patients already receiving such medications and there was absence of a control group, the individual contribution of ISTURISA or of antihypertensive and antidiabetic medication adjustments cannot be clearly established.3

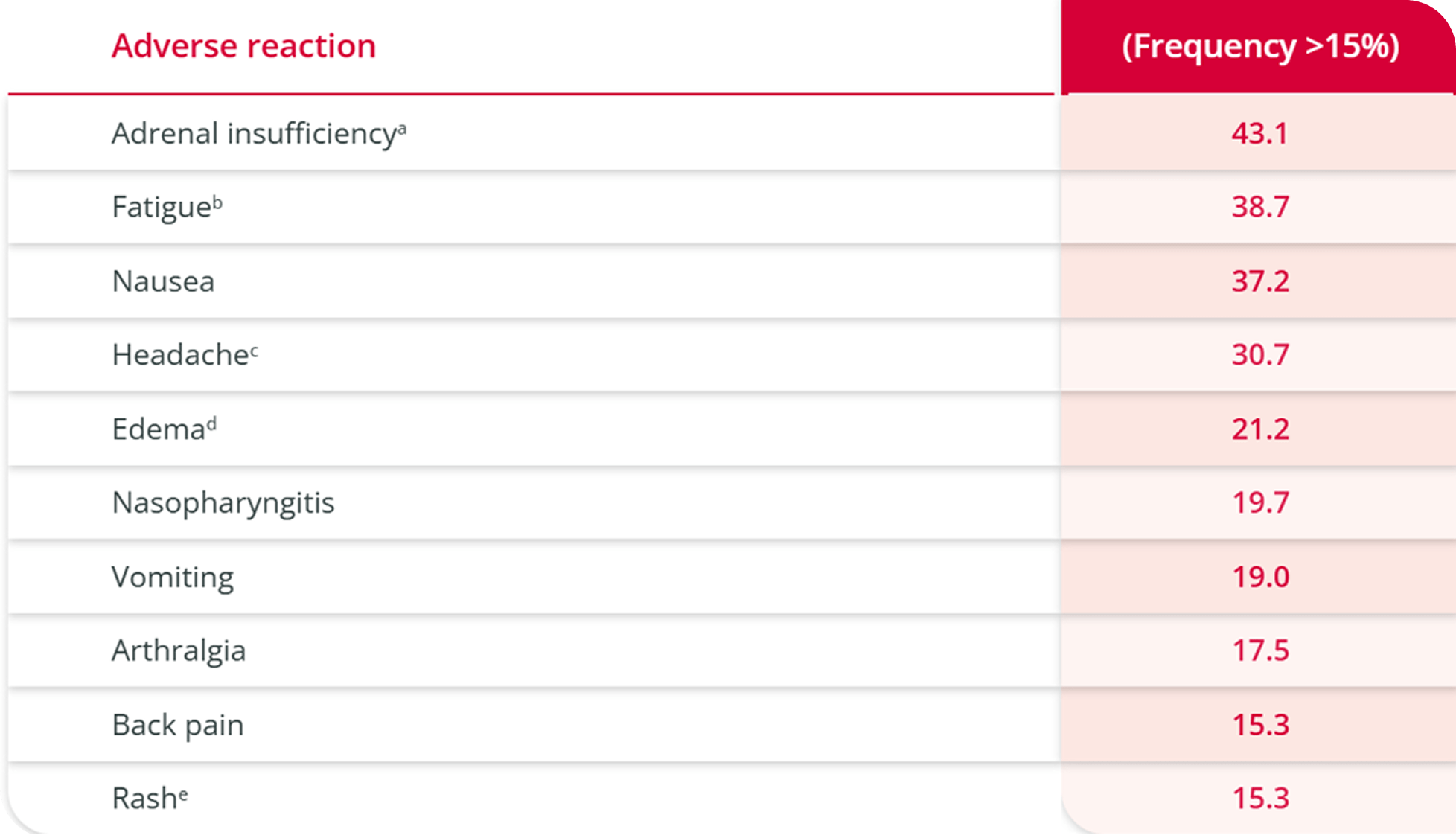

ISTURISA was well tolerated, with no new safety signals reported during long-term treatment6

A well-tolerated safety profile demonstrated through 48 weeks1

Adverse reactions among 137 patients

with Cushing’s disease (CD) who received at least 1 dose of ISTURISA in the study3

aAdrenal insufficiency includes glucocorticoid deficiency, adrenocortical insufficiency acute, steroid withdrawal syndrome, cortisol free urine decreased, cortisol decreased. One-third of the subjects with this event had low cortisol levels indicative of adrenal insufficiency. The majority of subjects had normal cortisol levels suggesting a cortisol withdrawal syndrome.

bFatigue includes lethargy, asthenia.

cHeadache includes head discomfort.

dEdema includes edema peripheral, generalized edema, localized edema.

eRash includes rash erythematous, rash generalized, rash maculopapular, rash papular.

Hirsutism was observed in 12% (13/106) of female patients.1,3 This adverse event was considered mild to moderate,fand no patient discontinued as a result.1

fMild to moderate = severity rated by investigator as 1 or 2 in the LINC 3 clinical trial.4

References

Sharma ST, Nieman LK, Feelders RA. Cushing’s syndrome: epidemiology and developments in disease management. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;17(7):281-293. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S44336 2. Lonser RR, Nieman L, Oldfield EH. Cushing’s disease: pathobiology, diagnosis, and management. J Neurosurg. 2017;126(2):404-417. doi:10.3171/2016.1.JNS152119 3. Giuffrida G, Crisafulli S, Ferraù F, et al. Global Cushing's disease epidemiology: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45(6):1235-1246. doi:10.1007/s40618-022-01754-1 4. Nishioka H, Yamada S. Cushing's disease. Clin Med. 2019;8(11):1951. doi:10.3390/jcm8111951 5. Feelders RA, Pulgar SJ. Kempel A, Pereira AM. The burden of Cushing's disease: clinical and health-related quality of life aspects. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;167(3):311-326. doi:10.1530/EJE-11-1095 6. Pivonello R, De Leo M, Cozzolino A, Colao A. The Treatment of Cushing's Disease. Endocr Rev. 2015 Aug;36(4):385-486. doi:10.1210/er.2013-1048 7. Nieman LK, Biller BMK, Findling JW. et al. Treatment of Cushing's syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. Endocrine. 2015;100(8):2807-2831. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-1818 8. Fleseriu M, Auchus R, Bancos I, et al. Consensus on diagnosis and management of Cushing's disease: a guideline update. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(12):847-875. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00235-7 9. Dekkers OM, Biermasz NR, Pereira AM, et al. Mortality in patients treated for Cushing's disease is increased, compared with patients treated for nonfunctioning pituitary macroadenoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(3):976-981. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-2112 10. Lacroix A, Feelders RA, Stratakis CA, Nieman LK. Cushing's syndrome. Lancet. 2015;386(9996):913-927. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61375-1 11. Fleseriu M, Castinetti F. Updates on the role of adrenal steroidogenesis inhibitors in Cushing’s syndrome: a focus on novel therapies. Pituitary. 2016;19(6):643-653. doi:10.1007/s11102-016-0742-1 12. Dekkers OM, Horváth-Puhó E, Jørgensen JOL, et al. Multisystem morbidity and mortality in Cushing’s syndrome: a cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(6):2277-2284. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-3582 13. van Haalen FM, Broersen LHA, Jørgensen JO, Pereira AM, Dekkers OM. Management of endocrine disease: Mortality remains increased in Cushing’s disease despite biochemical remission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172(4):R143-R149. doi:10.1530/EJE-14-0556

Let’s get started. Please let us know whether you are a patient seeking support or a licensed healthcare professional.

We value your privacy

To offer you a better browsing experience, we use cookies to analyze site performance, personalize content, and enable certain features. By continuing, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy.

Disclaimer

This site contains medical information that is intended for Healthcare Professionals only and is not meant to substitute for the advice provided by a medical professional.

All decisions regarding patient care should be made considering the unique characteristics of the patient.